Stylophone circuit

The topic of alternative keyboard layouts has gained traction due to advancements in Software and MIDI technology, making it practical to explore different configurations. This post aims to clarify what alternative keyboard layouts are, distinct from other methods of controlling synthesizers or generating musical notes. While there is overlap among these concepts, the focus here is on specific proposals aimed at enhancing the traditional piano and organ keyboard. These alternative layouts are appealing not only to non-players but also to trained keyboardists and those interested in music theory. The conventional piano keyboard, characterized by a linear arrangement of large white keys and thin black keys, poses challenges in terms of ergonomics and the learning process. It requires awkward hand positioning and limits access to certain musical scales. Historical attempts to innovate keyboard design date back to the 19th century, with the introduction of two-dimensional key arrangements. This design allows for repeated notes across different rows, closer spacing for larger intervals, and consistent chord patterns irrespective of the key. The term "isomorphic" is often used to describe these layouts, which were notably developed by Paul von Janko and Kaspar Wicki. Brian Hayden later created a similar system known as the Wicki-Hayden layout. This layout emphasizes diagonal relationships between notes and has influenced modern electronic instruments. Future discussions will delve into topics such as microtonality and dynamic tonality, as well as the evolution of instruments like the Jammer and the AxiS-49 keyboard, both of which utilize isomorphic designs.

The exploration of alternative keyboard layouts has been significantly influenced by technological advancements in software and MIDI, which facilitate experimentation with different configurations. Alternative keyboard layouts diverge from conventional methods of synthesizer control and musical note generation. While there is some overlap in these areas, the focus here is on specific innovations that aim to enhance the traditional piano and organ keyboard experience.

The conventional piano keyboard, with its familiar arrangement of large white keys and narrow black keys, presents several challenges. The ergonomic design necessitates an awkward arm position, and the linear key arrangement can make it difficult for players to reach octaves or play chords in various keys. Additionally, this configuration limits the ability to explore musical scales beyond the standard 12-note system commonly used in Western music.

Historical efforts to innovate keyboard designs began as early as the 19th century, when musicians and inventors proposed two-dimensional key layouts. Such designs offer numerous advantages, including the ability to repeat notes across different rows, closer spacing for intervals, and consistent chord patterns regardless of the starting key. This innovative approach is often referred to as "isomorphic," a term that describes the uniformity of chord shapes across the keyboard.

Notable isomorphic keyboard layouts include those developed by Paul von Janko and Kaspar Wicki in the 19th century, along with a similar system created by Brian Hayden in the 20th century, known as the Wicki-Hayden layout. These layouts emphasize the importance of diagonal relationships between notes, a feature that has been adopted in modern electronic instruments.

In addition to exploring these innovative designs, future discussions will address related topics such as microtonality, which allows for musical scales that deviate from the traditional 12-note system, and dynamic tonality, which offers greater flexibility in musical expression. Instruments like the Jammer and the AxiS-49 keyboard exemplify the practical application of isomorphic designs in contemporary music-making.

The ongoing evolution of keyboard layouts and their applications in modern electronic instruments underscores the significance of these innovations in expanding the possibilities of musical expression and accessibility for musicians of all skill levels.I`m not sure exactly which department this topic should go in, but I`ve added Software/MIDI` as the advent of these two things has made the possibility of using alternative keyboard layouts very much a practical proposition. I`ve been experimenting with these and come up with some relatively low-cost ways of trying them out.

The purpose of this po st is to explain what alternative keyboard layouts` are as opposed to alternative methods of controlling synths` or alternative methods of generating musical notes`, which I deal with elsewhere in the blog. Although there`s undoubtedly an overlap between these things, I`d like to talk here about some specific proposals that have been made over the years to improve the traditional piano/organ keyboard certainly appealing to those who are non-players of the instruments, but also with a specific appeal to trained keyboard players and those with a keen interest in music theory.

I`ll get into the music theory aspect, insofar as I understand it myself, later; and follow-up posts here will describe the different ways I`ve tried putting alternative keyboard layout ideas into practice. To begin at the beginning, the conventional piano keyboard, with its line of large white keys interrupted by thin black keys, although a familiar and iconic design, isn`t necessarily the easiest way to play or learn to play music: you have to hold your arms at an odd, straight-on angle to the keyboard; it`s a long stretch from one note to the next octave up or down; you have to move your hands to different positions to play chords in different keys, and so on.

Ultimately we might also consider how difficult it makes things if you want to play music using divisions of the musical scale which are different from the 12-note one we in the West are used to. It was a long time ago, certainly as early as the 19th century, when people began to think of replacing the one-dimensional line of keys found on pianos and organs with a two-dimensional bank of keys, like the bank of keys on a typewriter (or this computer keyboard I`m using now).

It was quickly realised that there would be more than one advantage to this arrangement: notes could be repeated in several places on different rows, allowing the player to find the easiest way to play a particular passage (players of stringed instruments are used to this and wouldn`t want to be without it!); notes which are far apart on the conventional keyboard could be placed closer together, enabling even those with small hands to play chords or melodic passages with large intervals; and, most importantly of all, the keys could be distributed in such a way that the pattern of a particular chord would be exactly the same, no matter which key it was played in, and the pattern of a melodic passage would be the same, no matter which note it started on. It is this latter feature which leads to the name often given as a description of this type of keyboard isomorphic`.

Well-known isomorphic keyboard layouts were invented by Paul von JankG³ and Kaspar Wicki in the 19th Century, and in the 20th Century, Brian Hayden independently developed a system similar to Wicki`s, which one often sees described as the Wicki-Hayden system. This is a picture of a piano with a Janko keyboard layout. As you can see, there are still white notes and black notes, but not in the same pattern as on a conventional piano, and there are 6 rows of keys: [Photograph of piano with Janko keyboard at the Musikinstrumenten-Museum, Berlin by Morn the Gorn (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.

0 ( ) or GFDL ( )], via Wikimedia Commons` ] This diagram of the Wicki-Hayden layout shows how the notes are placed in relation to one another. The keys themselves may be buttons, as they are on a concertina or accordion (Brian Hayden was a concertina player), but the hexagonal pattern used here emphasizes the importance of diagonal relationships between the notes, and relates to the method often used in modern electronic instruments of using hexagonal keys set out in exactly this way.

[Diagram of the Wicki-Hayden note layout used on some button accordions and some isomorphic button-field MIDI instruments by Waltztime (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons ] Each of these pages contains numerous links to external sites, if you`d like to know more. I`ll be dealing with some of the issues that follow on from this, such as microtonality (as mentioned above, these two-dimensional layouts also lend themselves more readily to musical scales of more or less than 12 notes) and dynamic tonality in future posts.

You should also check out this site: which is also the home of the program MIDI Integrator, which I have used, and an interesting modern-day electronic instrument using an isometric keyboard (two, in fact) called the Jammer. The Jammer, in turn, is a development along similar lines of an instrument called the Thummer which almost reached the point of commercial production and uses a keyboard called the AxiS-49, which is commercially available (from C-Thru Music at ).

A larger version of this keyboard, the AxiS-64 is also produced: All of these instruments these days are MIDI controllers, and YouTube is probably the best place to see them in action. This lengthy introduction to the AxiS-64 also serves as an illustration of many of the reasons why isomorphic keyboards were invented:.

You can also see the Thummer and the Jammer. There are hundreds more videos of these instruments and others, including a nice-looking Japanese synth called the Chromatone, which appears to be completely self-contained: The Stylophone, if you`ve never encountered one, is a small, hand-held monophonic instrument played by touching a stylus to a row of metal pads the edge of a large printed circuit board laid out like the keys of a piano. It was invented and first marketed in the 1960s, and is sometimes described as the world`s first mass-produced synthesizer.

In my view the Stylophone is an indispensable element in the arsenal of the electronic musician it`s simple, distinctive-sounding, and most types are available at a reasonable price, with patience, from charity shops or on eBay. It`s also possible to make a number of straightforward and some not-so-straightforward modifications to it.

I have described elsewhere in the blog some of the ones I`ve done. Although largely the brainchild of engineer Brian Jarvis, accounts of its genesis in 1967 suggest that the Stylophone would never have seen the light of day without the encouragement and input of brothers Burt and Ted Coleman who, together with Jarvis, ran a company called DG breq. DG breq produced equipment for the film and broadcasting industry and their name is said to derive from their specialities of DUBbing and RECording, with the umlaut and the q` added to give the firm more of an international air (or perhaps, like MotG¶rhead or MG¶tley CrG e, just to look cool!) The marketing masterstroke which ensured the eternal popularity of the Stylophone was the engagement of the multi-talented London-based, but Australian-born entertainer, Rolf Harris.

Even before production began, the Stylophone was introduced to the world on Harris`s popular Saturday TV show on the BBC, and, it is said, became an instant hit despite at first being available only by mail-order from DG breq at the frightening cost of 8 pounds 18 shillings and sixpence, around ninety-five pounds in today`s money! Over the following decade a number of different versions of the Stylophone were produced. I have a treble which is all white a standard black, and a bass also black. This latter wasn`t a production model, but the circuit diagram that came with the standard showed different component values for all these three types, so I modified a standard to produce the bass register, an octave below.

I`ve subsequently modified this to produce a further octave below that I call it The Double Bass` but this is not a modification suggested by DG breq themselves. There is also a later 1970 ²s version (the New Sound`) with a fake wood fascia in place of the familiar metal grille.

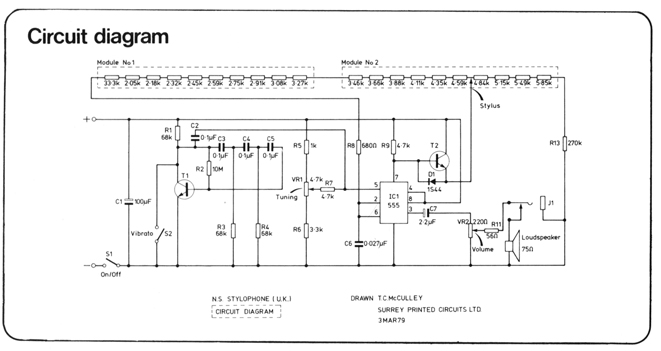

This latter has a feature noticeably absent from the earlier models a volume control, a useful feature in the days before the ubiquitous earphones. Here is the component layout and schematic/circuit diagram from the booklet which came with it. It was not long after this, in 1975 or thereabouts, when production of the original Stylophone ceased; and this might have been the end of the Stylophone story, had Brian Jarvis`s son Ben not had the idea in the early 2000s of bringing it back.

By 2007 the new Stylophone S1 was on sale, sufficiently similar to the original to be instantly recognisable, but with some updated features, including built-in input and output sockets and a three-way tone control. It`s possible to do modifications on all these variations on the Stylophone design, even the S1. Despite the fact that the chip that does all the work in the S1 is very tiny and inaccessible, parts of the pitch and vibrato circuits are available, and the output stage is on a separate PCB.

I was able to do some mods on a couple of these. The New Sound`, based on the very common 555 chip is easier to deal with, and I was able to do a lot with mine (see ). There are many circuits for 555-based oscillators in books and on the internet, and the 555 in the New Sound` is easily accessible for modding.

I haven`t done much with the original Stylophones but these should be even easier, as the resistors which fix the pitches of the notes are exposed, and it should be possible to do things to these without too much trouble. The biggest problem with the original and New Sound` Stylophones is likely to be the cost. Since these are sought after by collectors, they can fetch rather higher prices than you might want to pay for something which you intend to experiment on!

Many stars other than Rolf Harris himself have been publicly associated with the Stylophone. You can read about these on the Stylophone page in the Wikipedia at, and see pictures of them on Stylophonica, the official home of the Stylophone` at. You can also learn more of the history of the Stylophone at (or ), the Stylophone Collectors Information Site; buy a vintage Stylophone at, the Stylophone Sales Center; or even make your own Stylophone at !

You will also find out about the mighty Stylophone 350S, much larger than the ordinary Stylophone, with two styluses (styli ), more notes, more tones and a cunning light-sensitive filter/vibrato control. This also went out of production in the 1970s and has not so far been revived. 🔗 External reference

The exploration of alternative keyboard layouts has been significantly influenced by technological advancements in software and MIDI, which facilitate experimentation with different configurations. Alternative keyboard layouts diverge from conventional methods of synthesizer control and musical note generation. While there is some overlap in these areas, the focus here is on specific innovations that aim to enhance the traditional piano and organ keyboard experience.

The conventional piano keyboard, with its familiar arrangement of large white keys and narrow black keys, presents several challenges. The ergonomic design necessitates an awkward arm position, and the linear key arrangement can make it difficult for players to reach octaves or play chords in various keys. Additionally, this configuration limits the ability to explore musical scales beyond the standard 12-note system commonly used in Western music.

Historical efforts to innovate keyboard designs began as early as the 19th century, when musicians and inventors proposed two-dimensional key layouts. Such designs offer numerous advantages, including the ability to repeat notes across different rows, closer spacing for intervals, and consistent chord patterns regardless of the starting key. This innovative approach is often referred to as "isomorphic," a term that describes the uniformity of chord shapes across the keyboard.

Notable isomorphic keyboard layouts include those developed by Paul von Janko and Kaspar Wicki in the 19th century, along with a similar system created by Brian Hayden in the 20th century, known as the Wicki-Hayden layout. These layouts emphasize the importance of diagonal relationships between notes, a feature that has been adopted in modern electronic instruments.

In addition to exploring these innovative designs, future discussions will address related topics such as microtonality, which allows for musical scales that deviate from the traditional 12-note system, and dynamic tonality, which offers greater flexibility in musical expression. Instruments like the Jammer and the AxiS-49 keyboard exemplify the practical application of isomorphic designs in contemporary music-making.

The ongoing evolution of keyboard layouts and their applications in modern electronic instruments underscores the significance of these innovations in expanding the possibilities of musical expression and accessibility for musicians of all skill levels.I`m not sure exactly which department this topic should go in, but I`ve added Software/MIDI` as the advent of these two things has made the possibility of using alternative keyboard layouts very much a practical proposition. I`ve been experimenting with these and come up with some relatively low-cost ways of trying them out.

The purpose of this po st is to explain what alternative keyboard layouts` are as opposed to alternative methods of controlling synths` or alternative methods of generating musical notes`, which I deal with elsewhere in the blog. Although there`s undoubtedly an overlap between these things, I`d like to talk here about some specific proposals that have been made over the years to improve the traditional piano/organ keyboard certainly appealing to those who are non-players of the instruments, but also with a specific appeal to trained keyboard players and those with a keen interest in music theory.

I`ll get into the music theory aspect, insofar as I understand it myself, later; and follow-up posts here will describe the different ways I`ve tried putting alternative keyboard layout ideas into practice. To begin at the beginning, the conventional piano keyboard, with its line of large white keys interrupted by thin black keys, although a familiar and iconic design, isn`t necessarily the easiest way to play or learn to play music: you have to hold your arms at an odd, straight-on angle to the keyboard; it`s a long stretch from one note to the next octave up or down; you have to move your hands to different positions to play chords in different keys, and so on.

Ultimately we might also consider how difficult it makes things if you want to play music using divisions of the musical scale which are different from the 12-note one we in the West are used to. It was a long time ago, certainly as early as the 19th century, when people began to think of replacing the one-dimensional line of keys found on pianos and organs with a two-dimensional bank of keys, like the bank of keys on a typewriter (or this computer keyboard I`m using now).

It was quickly realised that there would be more than one advantage to this arrangement: notes could be repeated in several places on different rows, allowing the player to find the easiest way to play a particular passage (players of stringed instruments are used to this and wouldn`t want to be without it!); notes which are far apart on the conventional keyboard could be placed closer together, enabling even those with small hands to play chords or melodic passages with large intervals; and, most importantly of all, the keys could be distributed in such a way that the pattern of a particular chord would be exactly the same, no matter which key it was played in, and the pattern of a melodic passage would be the same, no matter which note it started on. It is this latter feature which leads to the name often given as a description of this type of keyboard isomorphic`.

Well-known isomorphic keyboard layouts were invented by Paul von JankG³ and Kaspar Wicki in the 19th Century, and in the 20th Century, Brian Hayden independently developed a system similar to Wicki`s, which one often sees described as the Wicki-Hayden system. This is a picture of a piano with a Janko keyboard layout. As you can see, there are still white notes and black notes, but not in the same pattern as on a conventional piano, and there are 6 rows of keys: [Photograph of piano with Janko keyboard at the Musikinstrumenten-Museum, Berlin by Morn the Gorn (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.

0 ( ) or GFDL ( )], via Wikimedia Commons` ] This diagram of the Wicki-Hayden layout shows how the notes are placed in relation to one another. The keys themselves may be buttons, as they are on a concertina or accordion (Brian Hayden was a concertina player), but the hexagonal pattern used here emphasizes the importance of diagonal relationships between the notes, and relates to the method often used in modern electronic instruments of using hexagonal keys set out in exactly this way.

[Diagram of the Wicki-Hayden note layout used on some button accordions and some isomorphic button-field MIDI instruments by Waltztime (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons ] Each of these pages contains numerous links to external sites, if you`d like to know more. I`ll be dealing with some of the issues that follow on from this, such as microtonality (as mentioned above, these two-dimensional layouts also lend themselves more readily to musical scales of more or less than 12 notes) and dynamic tonality in future posts.

You should also check out this site: which is also the home of the program MIDI Integrator, which I have used, and an interesting modern-day electronic instrument using an isometric keyboard (two, in fact) called the Jammer. The Jammer, in turn, is a development along similar lines of an instrument called the Thummer which almost reached the point of commercial production and uses a keyboard called the AxiS-49, which is commercially available (from C-Thru Music at ).

A larger version of this keyboard, the AxiS-64 is also produced: All of these instruments these days are MIDI controllers, and YouTube is probably the best place to see them in action. This lengthy introduction to the AxiS-64 also serves as an illustration of many of the reasons why isomorphic keyboards were invented:.

You can also see the Thummer and the Jammer. There are hundreds more videos of these instruments and others, including a nice-looking Japanese synth called the Chromatone, which appears to be completely self-contained: The Stylophone, if you`ve never encountered one, is a small, hand-held monophonic instrument played by touching a stylus to a row of metal pads the edge of a large printed circuit board laid out like the keys of a piano. It was invented and first marketed in the 1960s, and is sometimes described as the world`s first mass-produced synthesizer.

In my view the Stylophone is an indispensable element in the arsenal of the electronic musician it`s simple, distinctive-sounding, and most types are available at a reasonable price, with patience, from charity shops or on eBay. It`s also possible to make a number of straightforward and some not-so-straightforward modifications to it.

I have described elsewhere in the blog some of the ones I`ve done. Although largely the brainchild of engineer Brian Jarvis, accounts of its genesis in 1967 suggest that the Stylophone would never have seen the light of day without the encouragement and input of brothers Burt and Ted Coleman who, together with Jarvis, ran a company called DG breq. DG breq produced equipment for the film and broadcasting industry and their name is said to derive from their specialities of DUBbing and RECording, with the umlaut and the q` added to give the firm more of an international air (or perhaps, like MotG¶rhead or MG¶tley CrG e, just to look cool!) The marketing masterstroke which ensured the eternal popularity of the Stylophone was the engagement of the multi-talented London-based, but Australian-born entertainer, Rolf Harris.

Even before production began, the Stylophone was introduced to the world on Harris`s popular Saturday TV show on the BBC, and, it is said, became an instant hit despite at first being available only by mail-order from DG breq at the frightening cost of 8 pounds 18 shillings and sixpence, around ninety-five pounds in today`s money! Over the following decade a number of different versions of the Stylophone were produced. I have a treble which is all white a standard black, and a bass also black. This latter wasn`t a production model, but the circuit diagram that came with the standard showed different component values for all these three types, so I modified a standard to produce the bass register, an octave below.

I`ve subsequently modified this to produce a further octave below that I call it The Double Bass` but this is not a modification suggested by DG breq themselves. There is also a later 1970 ²s version (the New Sound`) with a fake wood fascia in place of the familiar metal grille.

This latter has a feature noticeably absent from the earlier models a volume control, a useful feature in the days before the ubiquitous earphones. Here is the component layout and schematic/circuit diagram from the booklet which came with it. It was not long after this, in 1975 or thereabouts, when production of the original Stylophone ceased; and this might have been the end of the Stylophone story, had Brian Jarvis`s son Ben not had the idea in the early 2000s of bringing it back.

By 2007 the new Stylophone S1 was on sale, sufficiently similar to the original to be instantly recognisable, but with some updated features, including built-in input and output sockets and a three-way tone control. It`s possible to do modifications on all these variations on the Stylophone design, even the S1. Despite the fact that the chip that does all the work in the S1 is very tiny and inaccessible, parts of the pitch and vibrato circuits are available, and the output stage is on a separate PCB.

I was able to do some mods on a couple of these. The New Sound`, based on the very common 555 chip is easier to deal with, and I was able to do a lot with mine (see ). There are many circuits for 555-based oscillators in books and on the internet, and the 555 in the New Sound` is easily accessible for modding.

I haven`t done much with the original Stylophones but these should be even easier, as the resistors which fix the pitches of the notes are exposed, and it should be possible to do things to these without too much trouble. The biggest problem with the original and New Sound` Stylophones is likely to be the cost. Since these are sought after by collectors, they can fetch rather higher prices than you might want to pay for something which you intend to experiment on!

Many stars other than Rolf Harris himself have been publicly associated with the Stylophone. You can read about these on the Stylophone page in the Wikipedia at, and see pictures of them on Stylophonica, the official home of the Stylophone` at. You can also learn more of the history of the Stylophone at (or ), the Stylophone Collectors Information Site; buy a vintage Stylophone at, the Stylophone Sales Center; or even make your own Stylophone at !

You will also find out about the mighty Stylophone 350S, much larger than the ordinary Stylophone, with two styluses (styli ), more notes, more tones and a cunning light-sensitive filter/vibrato control. This also went out of production in the 1970s and has not so far been revived. 🔗 External reference