bbc micro model b

Before the Atom was launched, executives at the BBC's education programming department, inspired by ITV's 1979 series The Mighty Micro, devised a plan to encourage the general public in Britain to learn about computer technology. The Mighty Micro, hosted by physicist Dr. Christopher Evans and based on his book of the same name, predicted how computer technology would significantly alter working practices and the economy in the near future. Dr. Evans observed the rapid growth of the computing industry in the United States, driven by companies like Apple and Commodore, which had captivated not only enthusiasts but had also begun transforming businesses. In 1979, the BBC produced a three-part series titled The Silicon Factor, which examined the social implications of the microchip revolution. In November of that year, the Corporation initiated preliminary work on a ten-part series, tentatively named Hands on Micros, scheduled for broadcast in October 1981. This series aimed to familiarize viewers with computers and encourage their use, marking the inception of what would be known as the BBC Computer Literacy Project (CLP), directed by The Silicon Factor's producer David Allen. In March 1980, the BBC began consulting to shape the Computer Literacy Project, engaging with the UK government’s Department of Industry, Department of Education and Science, Manpower Services Commission, and other organizations. Fortuitously, it learned that the Department of Industry planned to designate 1982 as the "Year of Information Technology." Consequently, it was determined that the Computer Literacy Project and the accompanying television series required a machine that the public could purchase and use to gain practical experience with the topics discussed in each episode. This approach aimed to ensure that the audience would fully engage with the new technology and achieve the objectives of the CLP. A comprehensive array of guides, adult learning courses, and software packages would be developed around this initiative. However, the BBC soon recognized that there was no standard platform available, particularly regarding Basic, the common programming language for home micros, which the show would utilize for programming demonstrations. Choosing an existing machine with its unique dialect of Basic could alienate viewers who opted for different machines. Therefore, the only viable solution was to establish a standard, specifying a machine that would incorporate a Basic variant with substantial commonality to other dialects while promoting good programming practices. The specifications would include all features a computer should possess, even if some, such as floppy disk and hard drive support, extended I/O options, and the ability to download programs via the Teletext system, were absent from many contemporary machines. To lend credibility to this "standard," it required the BBC's endorsement, which would necessitate close collaboration with BBC Engineering, the department responsible for the Corporation's technical projects. Developing a new machine from scratch was not feasible due to time constraints, as it would take at least two years, which exceeded the Computer Literacy Project's timeline. Thus, the CLP team decided to approach companies like Acorn and Science of Cambridge, which would later be renamed Sinclair Research. Ultimately, the BBC met with seven UK computer companies, six of which expressed interest in detailing their collaboration with the BBC and the machine they would produce. It has been suggested that the government influenced the BBC to select one particular company: Newbury Labs, which was owned by the government’s National Enterprise Board (NEB) and was developing a computer that could potentially meet the BBC’s requirements.

The BBC Computer Literacy Project aimed to democratize computer knowledge and skills among the British populace during a pivotal time in technological advancement. The initiative was grounded in the belief that widespread familiarity with computers would not only empower individuals but also enhance the overall economic landscape by fostering a technologically adept workforce. The project was characterized by a multifaceted approach that included television programming, educational resources, and the promotion of a standardized computing platform.

The Hands on Micros series served as a critical educational tool, designed to break down complex computing concepts into accessible lessons. This programming was complemented by the development of the BBC Microcomputer, which was intended to be user-friendly and widely available, ensuring that viewers could engage with the material presented in the series. The decision to create a standardized machine was particularly significant in an era where various computing platforms used different programming languages and interfaces. By establishing a common ground through the BBC Micro, the project sought to unify the learning experience and facilitate a smoother transition for individuals new to computing.

In summary, the BBC Computer Literacy Project was a forward-thinking initiative that recognized the transformative potential of computer technology. By combining educational programming with practical resources, the project aimed to equip a generation of Britons with the skills necessary to navigate and thrive in an increasingly digital world.Before the Atom had even been launched, executives at the BBC`s education programming department, enthused by rival broadcaster ITV`s 1979 series The Mighty Micro, developed a plan to help encourage ordinary Britons to learn to use computer technology. The Mighty Micro, presented by physicist Dr Christoper Evans and based on his book of the same n ame, had forecast how computer technology would utterly change working practices and the economy in the near future. He`d seen how the computing scene had exploded in the US on the back of kit from the likes of Apple and Commodore, and how it had not merely appealed to enthusiasts, but had also begun to transform business.

In 1979, the BBC produced a three-part series, The Silicon Factor, to explore the social impact of the microchip revolution. In November of that year, the Corporation began preliminary work on a ten-part series, provisionally titled Hands on Micros and scheduled to be broadcast in October 1981.

It would introduce viewers to the computer and help get them using one. It would also form the launch of what would become known as the BBC Computer Literacy Project (CLP), steered by The Silicon Factor Producer David Allen. In March 1980, the BBC began a consultation process to shape the Computer Literacy Project. It discussed the scheme with the UK government`s Department of Industry, the Department of Education and Science, the Manpower Services Commission, and other organisations.

By happy chance, it learned that the DoI was planning to name 1982 the `Year of Information Technology`. It was decided that the Computer Literacy Project and the TV series that would launch it needed a machine which the public could buy and use to gain hands-on experience of what was being discussed in each episode.

Only that way would the audience truly engage with the new technology and the goals of the CLP be realised. Around it would be assembled a full array of guides, adult-learning courses and software packages. However, the BBC quickly realised that, with no standard platform available, particularly when it came to Basic, the lingua franca of home micros and the language the show would be using to present examples of programming, it would have to specify one itself.

With currently available machines all sporting different dialects of Basic, it was felt that choosing one of them would hinder viewers who had bought a different machine. The only option, then, was to define a standard, to specify a machine that would incorporate a Basic that would have a great deal of commonality with other dialects, but would be well structured to foster good programming practice.

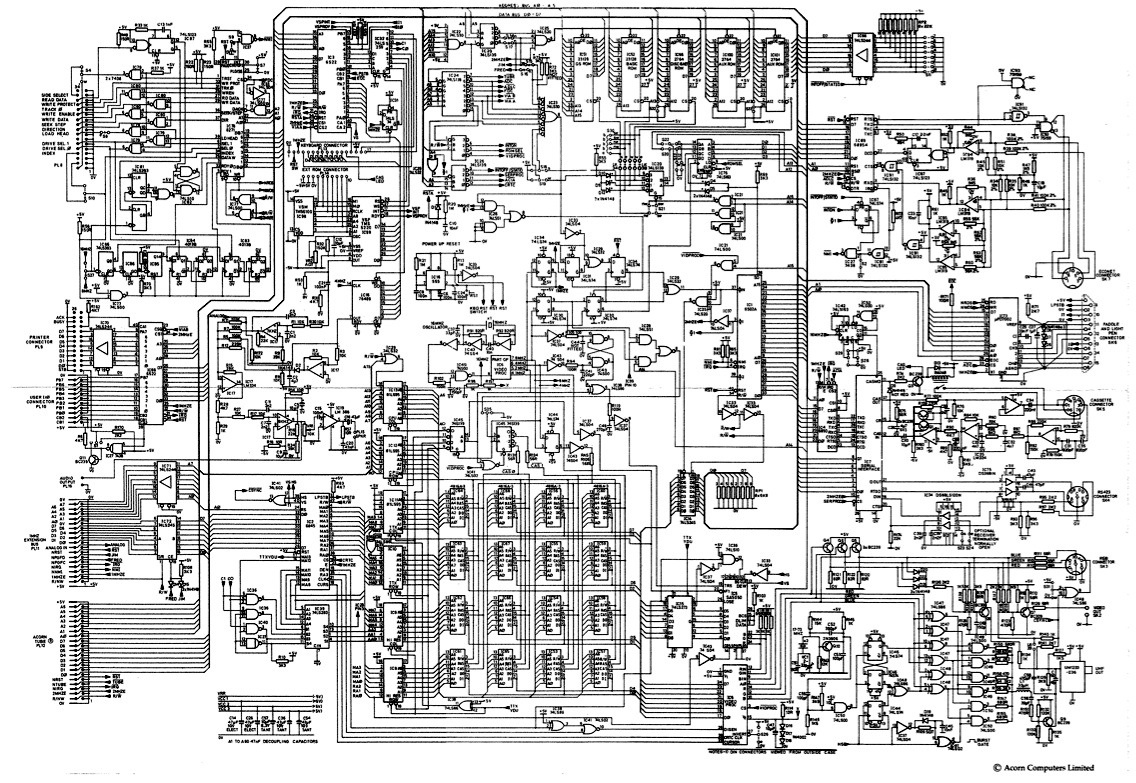

It would specify all the features a computer ought to possesses, even if those features such as floppy disk and hard drive support, extended I/O options, and the ability to download programs over the air through the Teletext system were absent from many current machines. It became clear that to give this `standard` some weight, it would need the BBC`s clear stamp of approval to be, in fact, the BBC Microcomputer.

That, in turn, would necessitate the close involvement of BBC Engineering, the department charged with handling all of the Corporation`s technical endeavours. Building a new machine from scratch was impossible it would take at least two years, more than the Computer Literacy Project schedule allowed.

So the CLP team decided to approach the likes of Acorn and Science of Cambridge soon to be renamed Sinclair Research. In all, the BBC met seven computer companies in the UK, six of whom were keen enough to detail how they would work with the BBC and the machine they would produce.

It has been claimed that the BBC was leaned on by the government to choose one company in particular: Newbury Labs. At the time, the government`s National Enterprise Board (NEB) owned Newbury, which was developing a computer that might meet the BBC`s needs and could certainly do with t

🔗 External reference

The BBC Computer Literacy Project aimed to democratize computer knowledge and skills among the British populace during a pivotal time in technological advancement. The initiative was grounded in the belief that widespread familiarity with computers would not only empower individuals but also enhance the overall economic landscape by fostering a technologically adept workforce. The project was characterized by a multifaceted approach that included television programming, educational resources, and the promotion of a standardized computing platform.

The Hands on Micros series served as a critical educational tool, designed to break down complex computing concepts into accessible lessons. This programming was complemented by the development of the BBC Microcomputer, which was intended to be user-friendly and widely available, ensuring that viewers could engage with the material presented in the series. The decision to create a standardized machine was particularly significant in an era where various computing platforms used different programming languages and interfaces. By establishing a common ground through the BBC Micro, the project sought to unify the learning experience and facilitate a smoother transition for individuals new to computing.

In summary, the BBC Computer Literacy Project was a forward-thinking initiative that recognized the transformative potential of computer technology. By combining educational programming with practical resources, the project aimed to equip a generation of Britons with the skills necessary to navigate and thrive in an increasingly digital world.Before the Atom had even been launched, executives at the BBC`s education programming department, enthused by rival broadcaster ITV`s 1979 series The Mighty Micro, developed a plan to help encourage ordinary Britons to learn to use computer technology. The Mighty Micro, presented by physicist Dr Christoper Evans and based on his book of the same n ame, had forecast how computer technology would utterly change working practices and the economy in the near future. He`d seen how the computing scene had exploded in the US on the back of kit from the likes of Apple and Commodore, and how it had not merely appealed to enthusiasts, but had also begun to transform business.

In 1979, the BBC produced a three-part series, The Silicon Factor, to explore the social impact of the microchip revolution. In November of that year, the Corporation began preliminary work on a ten-part series, provisionally titled Hands on Micros and scheduled to be broadcast in October 1981.

It would introduce viewers to the computer and help get them using one. It would also form the launch of what would become known as the BBC Computer Literacy Project (CLP), steered by The Silicon Factor Producer David Allen. In March 1980, the BBC began a consultation process to shape the Computer Literacy Project. It discussed the scheme with the UK government`s Department of Industry, the Department of Education and Science, the Manpower Services Commission, and other organisations.

By happy chance, it learned that the DoI was planning to name 1982 the `Year of Information Technology`. It was decided that the Computer Literacy Project and the TV series that would launch it needed a machine which the public could buy and use to gain hands-on experience of what was being discussed in each episode.

Only that way would the audience truly engage with the new technology and the goals of the CLP be realised. Around it would be assembled a full array of guides, adult-learning courses and software packages. However, the BBC quickly realised that, with no standard platform available, particularly when it came to Basic, the lingua franca of home micros and the language the show would be using to present examples of programming, it would have to specify one itself.

With currently available machines all sporting different dialects of Basic, it was felt that choosing one of them would hinder viewers who had bought a different machine. The only option, then, was to define a standard, to specify a machine that would incorporate a Basic that would have a great deal of commonality with other dialects, but would be well structured to foster good programming practice.

It would specify all the features a computer ought to possesses, even if those features such as floppy disk and hard drive support, extended I/O options, and the ability to download programs over the air through the Teletext system were absent from many current machines. It became clear that to give this `standard` some weight, it would need the BBC`s clear stamp of approval to be, in fact, the BBC Microcomputer.

That, in turn, would necessitate the close involvement of BBC Engineering, the department charged with handling all of the Corporation`s technical endeavours. Building a new machine from scratch was impossible it would take at least two years, more than the Computer Literacy Project schedule allowed.

So the CLP team decided to approach the likes of Acorn and Science of Cambridge soon to be renamed Sinclair Research. In all, the BBC met seven computer companies in the UK, six of whom were keen enough to detail how they would work with the BBC and the machine they would produce.

It has been claimed that the BBC was leaned on by the government to choose one company in particular: Newbury Labs. At the time, the government`s National Enterprise Board (NEB) owned Newbury, which was developing a computer that might meet the BBC`s needs and could certainly do with t

🔗 External reference