The Audionics CC-2 Amplifier

The Audionics CC-2 is named after Cliff Moulton, the chief engineer, and Charles Wood, the president of Audionics. However, the true designer of the amplifier is Bob Sickler, whose initials, "RLS," appear on the schematics. Following Bob's passing in Portland, it is important to acknowledge his contributions to the design of the amplifier, which played a crucial role in keeping Audionics operational during the late 1970s, with over 2000 units sold in the US and internationally. Many of these amplifiers are still in use today, and inquiries about repairs are still received. Repairing the CC-2 can be challenging due to the need to replace obsolete Motorola transistors with similar types and to adjust the feedback loop for the faster transistors.

In the mid-1970s, Audionics faced difficulties with an amplifier designed by Cliff Moulton, which had an alarming failure rate exceeding 50%. The PZ-3 amplifier often returned with extensive damage, leading to significant repair costs that threatened the company's viability. After six months, it was determined that the amplifier lacked sufficient phase margin and that the driver transistors were inadequately specified for their Safe Operating Area (SOA) current. This led to oscillations under certain loads, resulting in catastrophic failures. A temporary solution involved paralleling three driver transistors to address the SOA issue and to stabilize the amplifier further.

Despite the low distortion figures achieved in testing, the PZ-3 was criticized for its sound quality, which was perceived as harsh and gritty. This led to internal disagreements within the company regarding the amplifier's performance. The introduction of Bob Sickler, who was influenced by Matti Otala's theories on Transient Intermodulation Distortion (TIM), brought new perspectives to the design process. This marked a shift in the company's approach to audio engineering, as Sickler challenged the traditional views held by older engineers regarding feedback and distortion.

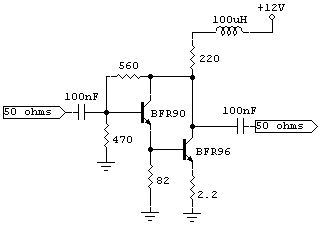

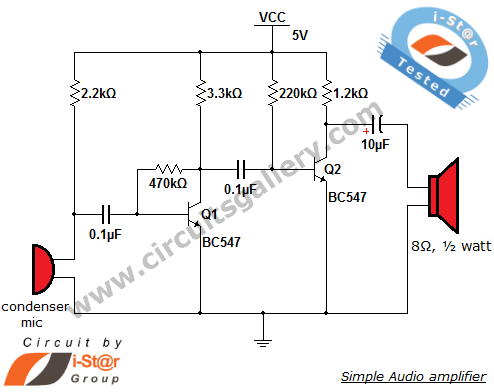

The Audionics CC-2 circuit design is characterized by its high feedback topology, similar to operational amplifiers, and low slew rate, which was typical of the era's amplifiers. The circuit includes multiple stages of amplification, with careful consideration given to the biasing of transistors to ensure stability and performance under various load conditions. The output stage typically utilizes complementary push-pull configurations to enhance efficiency and reduce distortion.

The design also incorporates protection circuits to prevent damage from overcurrent conditions, which were a significant concern due to the previously mentioned oscillation issues. These protection mechanisms are essential, particularly in applications where speaker loads may vary or be unpredictable.

In summary, the Audionics CC-2 serves as an important case study in audio amplifier design, illustrating the complexities of balancing performance, reliability, and sound quality. The legacy of Bob Sickler's contributions is evident in the continued use and repair of this amplifier, highlighting the impact of innovative engineering solutions in the audio industry.Although the Audionics CC-2 is named after Cliff Moulton (Audionics` chief engineer) and Charles Wood (Prez of Audionics), as usual in the business world, the principals in the company masked the identity of the real creator - Bob Sickler, whose name appears as "RLS" on the schematics. Since Bob passed away several years ago in Portland, the leas t I can do is give him the recognition he did not get at the time he designed the amplifier. This is the product that kept Audionics afloat in the late Seventies, selling more than 2000 copies in the US and overseas. There are still lots of people using them today, and I still get the occasional inquiry about repairing one.

Well folks, you are on your own, unless you find an engineer or technician sharp enough to replace the obsolete Motorola transistors with similar types and is smart enough to re-compensate the feedback loop for the faster transistors. Back to the story of the CC-2. In the mid-Seventies, Audionics wasn`t doing too well. The amplifier designed by Cliff Moulton was extremely unreliable, with a field failure exceeding 50%.

Some days we got back more blown-up amplifiers than we shipped out new. As anyone who`s worked in electronics repair knows, it takes a lot longer to fix something than build it in the first place - most of the cost of electronics is the labor to assemble it. So Cliff`s amp - the PZ-3 - was costing us a lot of money, and threatening the continuation of our jobs.

After six months CM finally figured out his amplifier didn`t have enough phase margin, and the driver transistors were underspecified for Safe Operating Area (SOA) current. So if the speaker load was just a little squirrelly (and lots of dealers used speaker-switchers then), the amp would enter brief modes of oscillation, which would then exceed the SOA of the driver transistors, and the next thing you know, BANG!

with a little wisp of smoke from the circuit board. Usually all of the driver, protection, and output transistors would be gone by the time we got it back. The somewhat kludgey fix was to parallel three driver transistors (taking care of the SOA problem) and slow down the amplifier just a bit more.

The PZ-3 was a pretty typical amplifier for the early Seventies - very high feedback, like a giant op-amp, very low slew rate (TIM distortion was then unknown), and questionable stability under dynamic loads. But the bench-test distortion figures into an 8-ohm resistive load were very low - in fact, the amplifier was named after its test figures, which was less than 0.

03% distortion. (PZ-3, get it Well, maybe it`s funny to an engineer. ) Needless to say, even though the problem was fixed, the initial impression in the market was kind of wary - also, in all honesty, it didn`t really sound that good, even though the distortion figure was lower than most other amps on the market. This state of affairs caused dissension in the company - Cliff thought that Charley and I were imagining things, while we thought that the PZ-3 didn`t really sound that good, being kind on the harsh and gritty side (although at this time we were all accustomed to first-generation transistor sound).

So the usual subjective/objective wrangle that has plagued audio in the following decades was right there in little Audionics on Sandy Boulevard in Portland. When Audionics moved out to Beaverton (a suburb on the West Side of Portland), Cliff and Charley hired a new technician, Bob Sickler.

Bob was not of the all-amps-sound-the-same school - he was excited by the theories of Matti Otala, who was exploring an entirely new form of distortion, Transient Intermodulation Distortion (TIM). Matti had started a culture war within the US audio-engineering community, and we saw it right inside Audionics.

The old-school engineers rejected the importance of this weird new form of distortion, and especially resisted the implicit criticism of negative feedback that Matti`s 🔗 External reference

In the mid-1970s, Audionics faced difficulties with an amplifier designed by Cliff Moulton, which had an alarming failure rate exceeding 50%. The PZ-3 amplifier often returned with extensive damage, leading to significant repair costs that threatened the company's viability. After six months, it was determined that the amplifier lacked sufficient phase margin and that the driver transistors were inadequately specified for their Safe Operating Area (SOA) current. This led to oscillations under certain loads, resulting in catastrophic failures. A temporary solution involved paralleling three driver transistors to address the SOA issue and to stabilize the amplifier further.

Despite the low distortion figures achieved in testing, the PZ-3 was criticized for its sound quality, which was perceived as harsh and gritty. This led to internal disagreements within the company regarding the amplifier's performance. The introduction of Bob Sickler, who was influenced by Matti Otala's theories on Transient Intermodulation Distortion (TIM), brought new perspectives to the design process. This marked a shift in the company's approach to audio engineering, as Sickler challenged the traditional views held by older engineers regarding feedback and distortion.

The Audionics CC-2 circuit design is characterized by its high feedback topology, similar to operational amplifiers, and low slew rate, which was typical of the era's amplifiers. The circuit includes multiple stages of amplification, with careful consideration given to the biasing of transistors to ensure stability and performance under various load conditions. The output stage typically utilizes complementary push-pull configurations to enhance efficiency and reduce distortion.

The design also incorporates protection circuits to prevent damage from overcurrent conditions, which were a significant concern due to the previously mentioned oscillation issues. These protection mechanisms are essential, particularly in applications where speaker loads may vary or be unpredictable.

In summary, the Audionics CC-2 serves as an important case study in audio amplifier design, illustrating the complexities of balancing performance, reliability, and sound quality. The legacy of Bob Sickler's contributions is evident in the continued use and repair of this amplifier, highlighting the impact of innovative engineering solutions in the audio industry.Although the Audionics CC-2 is named after Cliff Moulton (Audionics` chief engineer) and Charles Wood (Prez of Audionics), as usual in the business world, the principals in the company masked the identity of the real creator - Bob Sickler, whose name appears as "RLS" on the schematics. Since Bob passed away several years ago in Portland, the leas t I can do is give him the recognition he did not get at the time he designed the amplifier. This is the product that kept Audionics afloat in the late Seventies, selling more than 2000 copies in the US and overseas. There are still lots of people using them today, and I still get the occasional inquiry about repairing one.

Well folks, you are on your own, unless you find an engineer or technician sharp enough to replace the obsolete Motorola transistors with similar types and is smart enough to re-compensate the feedback loop for the faster transistors. Back to the story of the CC-2. In the mid-Seventies, Audionics wasn`t doing too well. The amplifier designed by Cliff Moulton was extremely unreliable, with a field failure exceeding 50%.

Some days we got back more blown-up amplifiers than we shipped out new. As anyone who`s worked in electronics repair knows, it takes a lot longer to fix something than build it in the first place - most of the cost of electronics is the labor to assemble it. So Cliff`s amp - the PZ-3 - was costing us a lot of money, and threatening the continuation of our jobs.

After six months CM finally figured out his amplifier didn`t have enough phase margin, and the driver transistors were underspecified for Safe Operating Area (SOA) current. So if the speaker load was just a little squirrelly (and lots of dealers used speaker-switchers then), the amp would enter brief modes of oscillation, which would then exceed the SOA of the driver transistors, and the next thing you know, BANG!

with a little wisp of smoke from the circuit board. Usually all of the driver, protection, and output transistors would be gone by the time we got it back. The somewhat kludgey fix was to parallel three driver transistors (taking care of the SOA problem) and slow down the amplifier just a bit more.

The PZ-3 was a pretty typical amplifier for the early Seventies - very high feedback, like a giant op-amp, very low slew rate (TIM distortion was then unknown), and questionable stability under dynamic loads. But the bench-test distortion figures into an 8-ohm resistive load were very low - in fact, the amplifier was named after its test figures, which was less than 0.

03% distortion. (PZ-3, get it Well, maybe it`s funny to an engineer. ) Needless to say, even though the problem was fixed, the initial impression in the market was kind of wary - also, in all honesty, it didn`t really sound that good, even though the distortion figure was lower than most other amps on the market. This state of affairs caused dissension in the company - Cliff thought that Charley and I were imagining things, while we thought that the PZ-3 didn`t really sound that good, being kind on the harsh and gritty side (although at this time we were all accustomed to first-generation transistor sound).

So the usual subjective/objective wrangle that has plagued audio in the following decades was right there in little Audionics on Sandy Boulevard in Portland. When Audionics moved out to Beaverton (a suburb on the West Side of Portland), Cliff and Charley hired a new technician, Bob Sickler.

Bob was not of the all-amps-sound-the-same school - he was excited by the theories of Matti Otala, who was exploring an entirely new form of distortion, Transient Intermodulation Distortion (TIM). Matti had started a culture war within the US audio-engineering community, and we saw it right inside Audionics.

The old-school engineers rejected the importance of this weird new form of distortion, and especially resisted the implicit criticism of negative feedback that Matti`s 🔗 External reference

Warning: include(partials/cookie-banner.php): Failed to open stream: Permission denied in /var/www/html/nextgr/view-circuit.php on line 713

Warning: include(): Failed opening 'partials/cookie-banner.php' for inclusion (include_path='.:/usr/share/php') in /var/www/html/nextgr/view-circuit.php on line 713